Metabolic Adaptation Part II: Cardio, Weight Training and Fat Loss

In part one of our blog on Metabolic Adaptation, we established that the speed at which one loses weight is largely determined by the size of one’s daily caloric deficit. How that deficit is created is a function of how much we eat (calories in), coupled with how much we move (calories out). Conventional approaches to weight loss typically marry a reduced calorie diet with an exercise program that is most often grounded in some type of aerobic exercise. Indeed, the American College of Sports Medicine recommends >150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise per week, coupled with a reduced calorie intake in order to enjoy clinically significant weight loss (1). The reason aerobic exercise is generally favored over weight training is based on the simple fact that aerobic exercise burns more calories per unit of time than weight training, and weight loss requires a caloric deficit. It stands to reason then that exercises that burn the most calories, will have the greatest effect on dai...

Metabolic Adaptation Part I: The Size of the Calorie Deficit

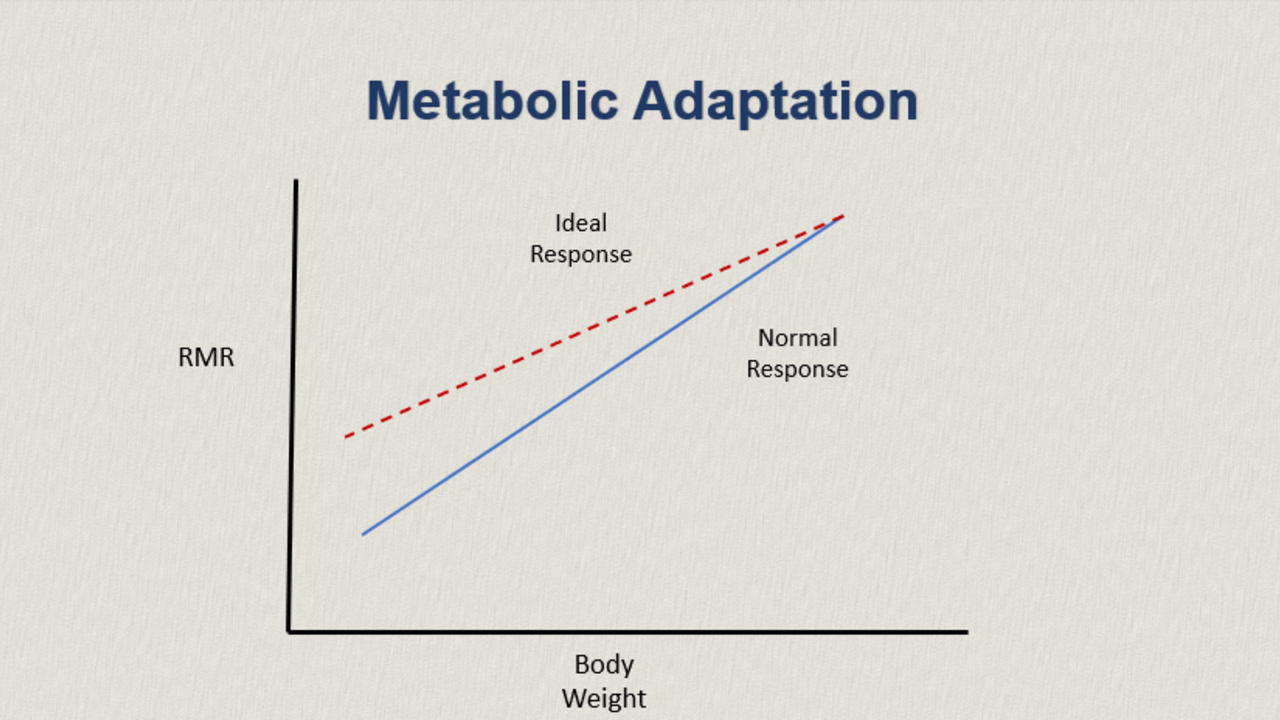

Metabolic adaptation is the abnormal slowing of the metabolism while in a calorie deficit for weight loss. The metabolism is directly influenced by one's body weight. As weight loss occurs, it is expected for the metabolism to slow down. It is widely accepted that metabolic adaptation occurs if the metabolism falls below 15 percent the predicted value when adjusted for body composition (1). Metabolic adaptation occurs if the metabolism falls greater than that during weight loss. A number of factors contribute to metabolic adaptation, but the two that seem to be most influential are the size of the calorie deficit and preservation or loss of lean mass during weight loss.

Weight loss does not always mean fat loss. The faster weight loss occurs, the more likely it is to include lean mass. Unfortunately it is expected that up to 25% of weight loss will come from lean body mass in people who are overweight or obese (2). Lean mass is significantly more metabolically active than adi...